So today is the day – Beethoven was born 250 years ago. At least, we think that date is correct; he was baptised on 17 December 1770, and it was customary to baptise babies within 24 hours of their birth.

Bonn’s newspaper today marks the anniversary; but Bonn is currently in lockdown, along with the rest of Germany and much of Europe. To hear Beethoven’s music at the present time in some countries, there are no current live performances in public venues; listeners must rely on radio, television, downloads, CD/record collections and the internet – or, better still, play it themselves on instruments at home.

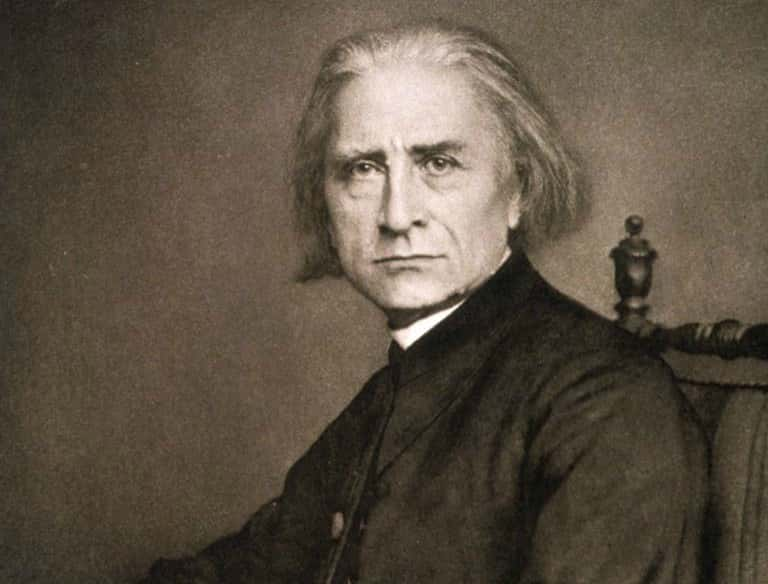

But let us go back to previous anniversaries; I have written about the 75th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, when his statue was unveiled in Bonn in 1845, and Liszt’s involvement, including the composition of a cantata in Beethoven’s honour.

What happened in 1870, 100 years after Beethoven’s birth? Was Liszt again involved in a celebratory concert?

Indeed, yes, in Weimar, and Liszt’s letters tell the story. To set the scene – the The Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein (ADMV) (General German Music Association) was the first national German musical association, founded in 1861 by Liszt and Franz Brendel. Its aim was to embody the musical ideals of the New German School of music and to promote the music of gifted composers. Its yearly gatherings were known as the Tonkünstler Versammlungen. In 1870, the four-day gathering celebrated Beethoven as well as composers such as Camille Saint-Saëns, who was invited to attend for the premiere of his cantata, Les noces de Prométhée .

The final festival concert on May 29th 1870 included the premiere of a second Liszt cantata in honour of Beethoven; “Zur Säkularfeier Beethovens” for soprano, alto, tenor, bass, choir and orchestra. It was composed in 1869-1870, with the text by German poet and literary historian, Adolf Stern; it was a revision and re-orchestration of Liszt’s first Beethoven cantata. Eduard Lassen had composed a Beethoven Overture which he conducted; Liszt conducted Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with his pupil Carl Tausig as soloist, and, after the interval, Liszt conducted Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

A Who’s Who of leading musicians of the time appears in Liszt’s correspondence and took part in different concerts in the festival. They include – Carl Rieder, a Leipzig choral conductor; one of his students at the Leipzig Conservatory was Heinrich Schulz-Beuthen. Eduard Lassen replaced Liszt as the court music director in Weimar in 1858. Karl Müller-Hartung was appointed music director in Weimar in 1865, becoming an important figure in the musical life of the city. Hans Feodor von Milde was an Austrian operatic tenor.

Ferdinand David was an experienced concertmaster (leader of the orchestra) in Leipzig, Hellmesberger a concertmaster in Vienna.

Hans von Bülow was a notable conductor and pianist, and he married Liszt’s daughter, Cosima, from whom he was later divorced.

Let’s follow the story … the date and place where each letter was written follow Liszt’s signature at the conclusion.

To C. F. Kahnt, the Music Publisher in Leipzig

… At the end of next week I will send you the piano-forte score of the Beethoven Cantata, and write full particulars to Riedel.

By the middle of April I hope to reach Weimar. Best thanks for sending the Ave maris stella—and in all friendliness I remain yours,

F.Liszt

Rome, February 14th, 1870

To Herr Gille, councillor of justice

Dear Friend,

The best thing I have to tell you today is that we shall soon see each other again. At the beginning of April I shall visit Bülow in Florence, and then go direct to Weimar.

Last week I had a correspondence with Riedel about matters of the Tonkunstler-Versammlung. The most important points are as follows:—The utmost economy that is possible to making a perfectly suitable orchestra and chorus. The spaces at our disposal in Weimar (churches, theater and refreshment room) will not allow of any great expenditure as regards the personnel. It is to be hoped that Müller-Hartung can obtain a respectable contingent for the Beethoven Mass, which will lessen the number of outside co-operators; and I in like manner reckon chiefly on the Weimar Vocal Union for the more important numbers of the concert programme – Psalm by Schulz-Beuthen, Prometheus by Saint-Saëns, my Beethoven Cantata, etc. The arrangement of the orchestra is to be as it was at the Carl August Festival and at the Tonkunstler-Versammlung of ’61 – 10 first violins, 6 to 7 double basses, etc. Riedel conducts Beethoven’s Mass; Lassen the concerts in the theater; and Müller-Hartung my Cantata. Conzertmeister David and Director Hellmesberger will preside over the 1st violins. Both gentlemen will also determine about the performance of the Beethoven Quartet. Any other special violin virtuoso would be superfluous this time. Riedel must arrange the distribution of the solo parts of the Beethoven Mass according as he thinks best. Milde only requires, in my Cantata,

“Dieser Brave sei verpflichtet

Das zu thun, was wir gedichtet.”

[“May this brave one be constrained

That to do which we ordained.”]

I flatter myself, by-the-bye, that Milde will also find a pleasure in the “Sternen-Cantabile”—

[Here, Liszt illustrates with a musical score excerpt where the words “Viel tausend halten nachtig” are sung. It contained the Cantabile in question for Milde from Liszt’s Beethoven Cantata.]

Riedel asks me who shall play the pianoforte?

If our meeting were at Jena I should decidedly invite Bülow to do it; he is the veritable Beethoven player and interpreter, the one who knows and who can do [Kenner und Konner]; but unfortunately the shades of Dingelstedt and Gutzkow warn him from Weimar’s doors…

Meanwhile there is no hurry about the choice of a pianist (he or she). Only arrange the principal things in a suitable manner, the chorus, orchestra, solo singers and the Beethoven Quartet; all the rest will soon be arranged after my arrival at Weimar in the middle of April.

Yours most faithfully,

F. Liszt

Villa d’Este, February 26th, 1870

(PS) The piano arrangement of my Cantata must be written out again, and cannot therefore be sent off for 8 or 10 days. The entire work lasts about three-quarters of an hour. I am so far ready with it, that there are only two or three more passages to be instrumented.

To Camille Saint-Saëns

Dear Friend,

The rehearsals of your “Les noces de Prométhée” (Marriage of Prometheus) are proceeding well at Weimar and Jena; we shall pay particular attention to the 4 harps, the saxophones, etc. But what is of the greatest consequence is yourself. I have announced your coming at the Court and in the town. A revoir then! Try to be here on the 24th, [on the 27th May, 1870, Saint-Saëns’ name appeared on the programme of these concerts. He also appeared as a pianist, and Liszt played with him at a Matinee on two grand pianos] – and believe me yours ever in sincere friendship,

F. Liszt

Weimar, May 12th, 1870

Had you been bidding at a Sotheby’s auction in 2017, with £2,000 to spare, you could have bought Liszt’s letter of 17 June 1870 to his publisher about the cantata – ZUR SÄKULARFEIER BEETHOVENS, written after the event, and, quoting from the online catalogue – ‘ providing him with information concerning the publication of the cantata, noting that there are a few things to re-engrave in the vocal score and to alter in the tenth plate, instructing him to engrave the score’s vocal parts as they appear in the vocal score, giving him details of the format and the dedication, stating that further instructions will be passed to him through Riedel, who is expected on Sunday, and asking for two copies of the Goethe March to be sent to Schuberth (“…Im Clavier Auszug derselben sind noch ein paar kleine Dinge nachzustechen…”)

Tausig’s performance of the concerto was described as ‘great and mighty’, and Liszt’s account of the 9th Symphony electrified everyone. The concert was a fitting tribute to Beethoven, whom Liszt had met in person, and a marvellous celebration of Beethoven’s centenary.

So Happy Birthday, dear Ludwig. Here’s to your 275th Anniversary in 2045 …

.